On the other hand, Kabir Khan’s directorial interventions are purposeful. The “king of single screens” has always shared a special affinity with the urban proletariat and non-metropolitan audiences of which the subaltern Muslim has been a significant part. The utopian finale, uninhibitedly emotive, is the staging of a dream nurtured by many in South Asia.Įid celebrations are incomplete without a Salman Khan release. One such example is Shahida’s home-coming that Bajrangi is unable to witness but which a joyful Chand Nawab records with his camcorder. The affective universe of the film is driven by some of Bombay cinema’s best loved conventions – a lost-and-found narrative, accidental partings, coincidental meetings and happy reunions. The romp through Pakistan is as hilarious as it is moving.

He also discovers that honesty is not always the best policy. In one sequence, Bajrangi self-righteously refuses to enter a masjid in Pakistan but quickly changes his mind when he spots a police van approaching. The two make common cause even though Bajrangi has no idea what “watan parast” means and Chand Nawab struggles to pronounce “desh bhakt.” The search for Munni’s parents drives Bajrangi into spaces that are anathema to him.

Film bajrangi bhaijan tv#

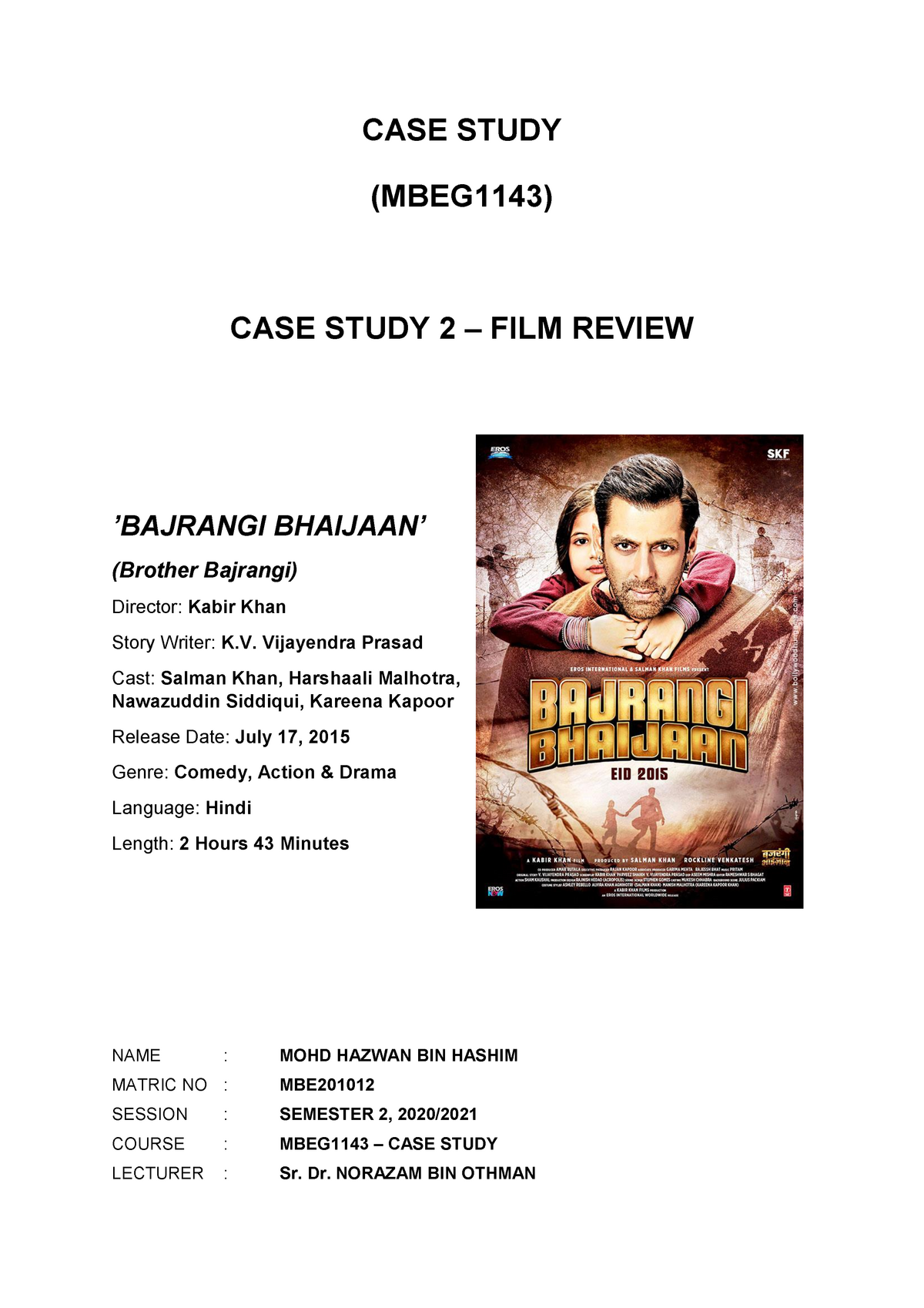

As illegal entrants into the country, the duo find a friend and accomplice in TV stringer Chand Nawab (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) whose introduction is a hilarious reconstruction of the real namesake’ s unedited piece-to-camera that had gone viral on the net in 2008. The journey to the cinematic Pakistan (shot on the Indian side of the border) transforms Bajrangi while recalibrating the representation of Pakistan in mainstream Bollywood films. When the Pakistan Embassy shuts down after an unruly attack by the saffron-brigade, the youngest member of the family is delighted that Munni’s stay in their house has been extended. The rest of the family is happy to have Munni around. Rasika disapproves of her father’s mindset and reprimands Bajrangi for sharing his views. But Dayanand’s bluster doesn’t command obedience. When he gets to know that Munni (Shahida) is a Muslim from Pakistan, he asks her to be removed forthwith. He does not like the smell of non-vegetarian cuisine to contaminate his pure vegetarian air.

He does not allow “Mohameddans” to rent rooms in his building. Rasika’s father Dayanand (Sharad Saxena) is a proud bigot. No wonder that his father, even after his death, glowers at him from the framed picture on the wall. Pawan modestly declares,” “In all the subjects that were dear to my father, I had absolutely no interest.” Bajrangi certainly does not embody the manhood valorised by the Hindu Right. Worse, when his father stands on the RSS stage singing to the glory of a strong Hindu nation, Pawan is the only fidgety boy in the long line of disciplined cadres. He is inept at wrestling because he is ticklish. He is disastrous in studies, taking 20 years to reach class 10 and finally graduating on his 11 th attempt. In fact, Pawan is a huge disappointment to his father who heads the RSS shakha of Pratapgarh. Neither Pawan nor Rasika (Kareena Kapoor), the woman he loves, share the bigotry of their Hindutva-enthused fathers. In Bajrangi Bhaijaan, Hindutva meets its nemesis right at home. The rest of the film is about “Bajrangi’s” growing attachment to the child, his efforts to take her home to Pakistan and his education about “paraya dharam”- the religion of the other. The man is “Bajrangi” Pawan Kumar Chaturvedi (Salman Khan), an acolyte of Hanuman. Shahida’s grandfather hopes that somewhere in India is a good man ( “khuda ka nek banda”) who will look after her. She cannot speak even though she can hear perfectly well. The difficulty of searching for a lost child across the border is made harder by Shahida’s speech impairment. On their way back, she wanders out of the Samjhauta express and gets left behind.

Six year old Shahida (Harshaali Malhotra), comes to India with her mother to visit the shrine of Nizamuddin Auliya. But by the time the film ends, “Bajrangi” has been effectively hijacked by “Bhaijaan” inaugurating the possibility of new associations.īajrangi Bhaijaan is the story of an unlikely friendship and a journey of discoveries. For Muslims, as indeed for many of us, the word “Bajrangi” had become inseparable from Babu Bajrangi, convicted of mass killings in Naroda Paitiya and the belligerent foot-soldiers of the Bajrangi Dal. When Salman Khan makes his flamboyant entry in Bajrangi Bhaijaan dancing in front of an enormous idol of Hanuman, the film may seem like a misplaced Eid offering.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)